Garrison Creek got its name because, when Toronto was young, it entered Lake Ontario just east of Fort York, the military garrison for the region. It is said that at that time, the mouth of the creek was suitable for mooring a few small boats.

Garrison Creek arose in two small stream north of St. Clair Avenue West. The eastern one, called here the Humewood Reach, had its source off Vaughn Rd. at Wychwood and Valewood Ave. The western, Springmount Stream, had its origin near Earlscourt Ave. and Morrison Ave, west of Dufferin. They joined together just north of Davenport Road and flowed south through what are now Christie Pits, Bickford Park, Fred Hamilton Park, Trinity Bellwoods Park, to enter Toronto Bay at Old Fort York. It was 7.7 km long and had several tributaries. It was also known as Bull’s Creek in the upper portions as it passed through farms owned by members of the Bull family.

Garrison Creek is divided into four reaches in this account: The Humewood Reach from the source near Vaughn Rd. to Davenport Rd. and the Iroquois Escarpment; The Christie Reach from there to Harbord Street; The Trinity Reach from Harbord Street to Queen St. and The Fort Reach from Queen Street to the lake. The nine tributaries (9 km) described here are: Springmount Stream, London Stream, Dewson Stream, Asylum Stream, Stafford Stream and the longest (2.5 km) Denison Creek which had Tributaries of its own including: Brock Stream, Havelock Stream and Moutray Stream.

The creek had its beginnings about 12,000 years ago when the last remnants of the Wisconsinan Glacier melted off the St. Clair West lands. The glacier had moved to and fro across this area for at least 60,000 years. It had wiped the land clear of forests and left deep deposits of glacial drift (sand, clay, gravel and stones) perhaps 200 feet thick. Post-glacial Lake Iroquois, the forerunner of Lake Ontario, washed against this pile of drift and created a steep bluff, the Lake Iroquois Shore Bluff, along what is now Davenport Road.

As the great ice sheet continued to melt back, the St Lawrence valley became free of ice and the waters in the Ontario basin dropped to a lower level. Garrison Creek then cut a longer course across the newly dry land to Lake Ontario.

For thousands of years, rain and melting snow drained off the sandy drift. At first, heavy storms would have created roaring torrents that cut quickly and deeply into the soil because there was no vegetation to retard the flow. Recent history indicates that we can expect a storm of the intensity of Hurricane Hazel once every hundred years. That suggests that, during the past 12,000 years , up to 120 storms of Hurricane Hazel’s intensity may have occurred. Each one would have deepened and widened the valleys until they reached the form we see today in Trinity Bellwoods Park and along streets such as Springmount Avenue north of Regal Road.

During those 12,000 years, vegetation slowly re-established. Forests of pine, oak, and locust eventually covered the area. Aboriginal peoples hunted in the area and travelled on the beach trail, now Davenport Road. In the 1800’s, land was cleared for farms and estates like “Earlscourt”, “Humewood” and Bartholomew Bull’s farm. With settlement, the creek began to suffer. By the early 1900’s, settlement had become so dense and the creek so polluted with sewage and refuse that sewers became essential for public health reasons. By the mid 1920’s the creek had been completely buried.

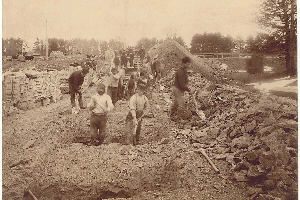

Digging sewer along Garrison Creek in 1890s

The creek is gone, but it is not forgotten. A large part of the rain and snow that falls in St. Clair West drains off our roofs and pavements into the sewers and can be heard rushing along under the roads after a storm. Because most of our sewers carry sanitary sewage as well as storm water, what we hear in the sewer in dry weather is basically sanitary sewage from our homes. That part of the rain and snow that does not run into the sewers, evaporates into the air, or percolates into gardens and green spaces to become part of the great ground water system that moves slowly below us toward Lake Ontario.

New interest in Garrison Creek arose in the 1980’s and 1990’s when it became clear that the combined storm and sanitary sewers that had been constructed, beginning in the late 1800’s, were too small to properly service modern development. During heavy storms, the combined effluent overloaded the sewers and the treatment plants, frequently resulting in sanitary sewage overflowing untreated into the lake. Beaches became polluted and swimming in the lake had to be stopped after rain storms. Very large capital expenditures were made to construct huge underground reservoirs to temporarily retain sewer water until it can be let it out slowly to sewage treatment facilities.

Citizen groups and municipal councils have recently taken increased interest in the history of the creeks, rivers and sewers and possible means of reducing sewer overflows. In 1997, citizens living in the St. Clair West area became interested in the history of the headwater valleys of Garrison Creek. They collected old maps and involved City planners, landscape architects, a civil engineer, a forester and others, to find traces of the old creek valleys in the headwater areas north of Dupont Street. As a result of these efforts, new mapping has been prepared showing that the east branch rose near the present site of Humewood School and the west branch rose in a shallow bowl of land south-east of the intersection of Earlscourt and Morrison Avenues.

Volunteer groups have developed in Toronto to focus public attention on heritage, storm water, community planning and urban design implications that arise from increased understanding of the history of creeks and “lost” creeks. In St. Clair West, the Garrison Creek Headwaters Committee, working under the leadership of David Raymont advises the City of Toronto, via the Garrison Creek Steering Committee, of the wishes of the people of their area on heritage and planning matters related to Garrison Creek. Communities along the creek alignment would like to see parts of the Garrison Creek Ravine system restored and are encouraging a greater understanding of the Ravine’s place in our bio-region. Some are working to create a series of stormwater management ponds that will recall the original creek; to restore several buried bridges; to find ways to bolster business, in collaboration with local merchants, by encouraging the public to enjoy the regenerated Ravine system; and to conduct an inventory of trees and flora in the ravine area.

In 1996, the City of Toronto passed a resolution calling for the revitalization of the Garrison Creek Ravine System. It has also been designated an area of capital concern. An interdepartmental committee has been struck to begin discussions as to how the revitalization of the Creek will unfold. Local neighbourhood groups, including Garrison Creek Community Group, will take part in this process. John Sewell was successful in receiving funding from a foundation to carry out a public consultation. Toronto City Council approved the Garrison Creek Linkage Project Status Report on Oct. 6, 1997. This report will provide guidance to the City and the Garrison Creek community for developing and implementing initiatives to assist in the revitalization of the Garrison Creek area.

Thanks to Dick Watts for much of this information.

The Garrison Creek Discovery Walk traces the path of the buried Garrison Creek Ravine and explores parklands, traditional neighbourhoods and vibrant main streets along the way. Although you can begin this Discovery Walk at any point along the route, a good starting point is Christie Pits Park, across the street from the Christie Subway station. The route leads you southward along the now-buried Garrison Creek Valley from the park down to Lake Ontario. You’ll visit other parks including Trinity Bellwoods and one of Toronto’s premier historical sites, Fort York.